A number of people liked my previous blog about Palestine, and here’s a related one from the same unpublished 2011 book Blogging in Bethlehem. It’s about women’s empowerment courses at the Hope Flowers adult education centre in Deheisheh, Bethlehem.

Monday 6th June 2011, Bethlehem, Palestine

“Where is your wife?” I was being asked this by a lively young lady of about eighteen who wore the full niqab. Not many women in Palestine wear them (Palestinians don’t like religious extremism), and most of them are young. “Er, I have no wife…”. It was tricky to explain further. “Oh, I am sorry.” I guess she assumed I was a widower. It was one of those situations where cultures scrape against one another, and there was no opportunity right then to reconcile the dysjunction.

She liked me and spoke good English – a thoroughly modern young woman. Her sparkly eyes shone through the narrow gap in her niqab. Her mother, wearing a normal headscarf or hijab, came up, visibly proud of her rather intelligent daughter, who was busy explaining to me how Islam is the only truth and how I ought to become a Muslim. She pointed out some verses in the Qur’an (though it was in Arabic, so I pretended to understand) and, rather touchingly, she gave me her own pocket Qur’an. This was an honour, a gift from the heart, I could tell.

In an Islamic kind of way, this young lady is a feminist. Wearing the niqab demonstrates her reservations about modern ways and the sexual and psychological pressures modern women experience. She wasn’t doing it for her parents (I checked later) – it was her own teenage life-choice. This movement of young Islamic women has some parallels to the bra-burning feminists of my generation many years ago, declaring that they are not just the appurtenances of men.

I had been at a women’s empowerment course at the Hope Flowers Centre for adult education at Deheisheh. Deheisheh is a part of greater Bethlehem (population 100,000), dominated by a large refugee camp, a community for the underprivileged. The Issa family had once lived there and worked their way out of it, and they deliberately put the centre there. The thirtyish women on the course came mainly from surrounding villages, with some from refugee camps and a number of educated women from Bethlehem. Some were illiterate and some had degrees, and Hope Flowers intentionally mixes them so that they can share the relative merits of both education and the lack of it. Apparently the educated ones initially had reservations, but these soon disappeared.

Today the subject was food hygiene. The purpose is to give women the necessary training to start cooperatives and create work for themselves. They were studying microbes, hygiene and infections, as well as nutritional issues, proteins, carbohydrates and balanced diets. They discussed the E. coli

outbreak in Europe at that time, fascinated that even in hygienic, chlorinated Germany and Britain such infections could occur. I told them that this is one of the consequences of industrial-scale food production.

The lecturer, Ibrahim Afaneh, who had done his doctorate in Belfast in the late 1990s, was brilliant. He had them enthused. He knew his stuff about good practice and quality control in food production, and he had good teaching technique, eliciting the ladies’ engagement and existing knowledge, getting various of them to teach what they knew to the others. When someone made a good contribution, everyone would clap.

This is only one segment of the women’s course. Another concerns group counselling, family therapy and self-development. Tomorrow, Tuesday, I’m also going down to Yatta, south of Hebron, with Ibrahim Afaneh, to watch another course in progress. Many of these women are so poor that providing for their transport is a vital ingredient in guaranteeing attendance. But enthusiasm levels are so high that it strikes me the women don’t need much incentive, only help getting there.

Ibrahim Afaneh invited me to speak and, though I had reservations as a man about teaching on a women’s empowerment course, it was clear that, to them, this was a unique opportunity because I was behaviourally non-sexist, and they loved having me around. Ibrahim, who had lived some years in Britain and also had it in his nature, as many of the more liberal Palestinian men do, was pretty good at non-oppressive male behaviour too. He was training women to do his job.

I shared some of my knowhow acquired from being a longstanding wholefood vegetarian. They didn’t know that the best source of protein is nuts (plenteous in Palestine), or that sesame seeds and tahini, a dietary standard here, provide the full range of amino acids which themselves facilitate the absorption of other proteins. At one point I asked them what the most important ingredient in cooking is. They suggested quality sources of foodstuffs, hygiene in kitchens, balanced diets… and then, after a pause, one of the illiterate women said, in Arabic, immediately translated, “The whole of your being”. Yes! She was closest to the point I was making: love. “If you cook with love, you bring Allah into the food, you heal people and it’s just like painting a picture or making music.” They all laughed, nodded and clapped.

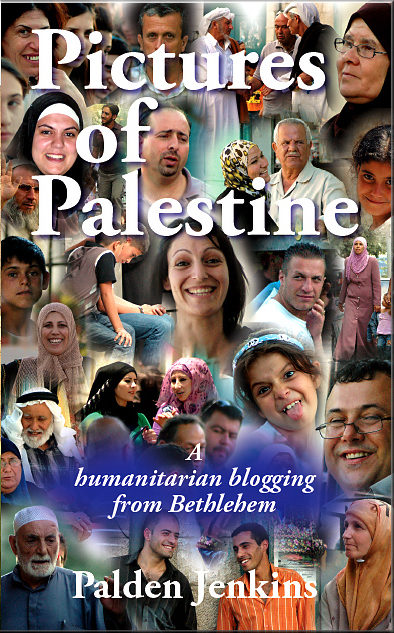

We had a great time. I took lots of photos. I shall write a report for the course’s UK funders, who have thus far provided 80,000 GBP over three years. A Quaker trust connected with Clark’s, the shoemakers, they fund women’s empowerment projects throughout the Muslim world. They are one of the few funding sources for Hope Flowers who have been steady, understanding, progressive and non-neurotic in their approach to funding.

Here I could see what was really happening at this course. These women aren’t fools, and they are not dazzled or easily tricked: they have a large fund of commonsense, they’re highly motivated and, were there anything spurious about these courses, they would leave like a shot. But no, they were excited, bubbling, rapt, eager to engage – and clearly their acquired knowledge would spread around their communities, leveraging the educational effect of the courses. Which is precisely what Hope Flowers sets out to do: it has a social philosophy of setting out to strengthen society.

Several women had turned up late, wanting to join, following reports from their friends. Maram (Ibrahim Issa’s wife), who runs the courses, told them the course was ending so there was no point, but they insisted and joined in. The young lady in the niqab and her mother were two of them, and later they emerged inspired. What I read from this was that observant Muslim women, while their ideas about self-development might not accord with those in the West, nevertheless are taking the modern world by the horns and striving to make something of it, but within their own context and way of seeing things. Modernity doesn’t involve just emulating the West.

Ibrahim Afaneh invited me to introduce myself. I told them I had started out in my adult life in the revolutions of the late Sixties, that I understood and supported the recent revolutions in the Arab world and, though I was British, I did not on the whole agree with the government and conventions of my own country. They loved that. So did I! I must confess that it is good to be welcomed and respected for this since, in Britain, being a dissident brings disadvantage, it’s a disqualifier and a source of disrespect. Being a dissenter here is seen as the sign of respect. But I felt duty-bound to bring them some tougher truths too.

Talking about proteins and nutrition, I mentioned how meat production uses up far more resources and land than what is involved in production of vegetable proteins. The seas are being fished out too. This is unsustainable. Something must change with protein consumption worldwide. Throughout history, most people have been 90% vegetarian and 10% meat-eating – meat and fish are dietary supplements, and their over-use today ruins the Earth. During my lifetime the world’s population had swollen from three to (in 2011) seven billion, and industrial meat-production and fishing cannot continue as they do if humanity is to survive in peace, justice and decency.

Much nodding: they knew this, but I think they appreciated someone articulating it clearly. I added that I had no stomach hanging out in front of me because of my chosen diet. Immediately there was excitement: it turned out that one-third of the women had lost weight in the last two months as a result

of dietary changes they had made in connection with the course. One woman said, “Look, the happy in me!”. She had lost twelve kilos. This training had significant consequences for the ladies – and other segments of the course included counselling, family therapy and open discussion of women’s issues which, for many, was the first time they had encountered this. This was a liberation course, tailored to them.

Finally I said that they will know that peace and justice have come when men do a lot of the cooking and raising of families. This raised the roof! As a Western eccentric I can get away with saying things like this, but I’ve also been privileged to be part of an historic change in gender balances in the West, even though it has at times been hard, and men like me, only 25 years ago, were still branded as failures and wimps.

Tomorrow I go with Ibrahim Afaneh to Yatta, south of Hebron, to witness the women’s empowerment course there. Yatta is an area where there are many illegal land-appropriations by Israeli settlers, and Palestinians there feel ignored and marginalised, out of the world’s sight. The area has many Bedouin, who sit at the very bottom of the apartheid pile in this segmented land. Many of their villages are unrecognised and deemed illegal, especially when they stand in the way of Israeli expansion.

This afternoon, having only just arrived back in Bethlehem, I went around town buying pots, pans, utensils, a lamp and other bits for the apartment where I am staying. I had done this two years ago too, but they are all gone – dispersed no doubt around the building or down some community black hole. This is one of the challenges of operating in Palestine – it’s a high-level chaos zone, and if you like order, you’ve got problems. It’s partially to do with Arabic cultural elasticism, to put it politely, and partially to do with living under occupation. Conflict has thrown Palestinians into a mindset of perpetual firefighting, living quite spontaneously without plans, systems and rules. So, when someone walked into my apartment while it was empty, seeing something useful, they ‘just borrowed’ it – and perhaps someone else just borrowed it from them, and off it went and was put, no doubt, to good use somewhere else. I hope the kit that I have just bought stays in the apartment in future. I’m going to get a Bedouin rug too – make the place more comfortable.

Later I had another challenge. Arriving back home tired, it took me fifteen minutes to realise that the reason the kettle wouldn’t work was that the electric trip-switch had killed the power. Then, later, with cuppa in hand, I fired up my computer to start uploading my blog entry and found the internet router downstairs was dysfunctional too. Of course, predictably I had no key to access the router. Another exercise in existential flexibility. Hopefully I can do the uploading tomorrow morning before heading off to Yatta.

We have internet apartheid here. Israel has hot fibre optics linking it with the West. But Palestinian internet goes by slower microwave transmission to Jordan – the Israelis won’t permit fibre optics or anything more than 3G mobile connectivity – then down to Dubai, where a big fibre-optic ‘pipe’ leads through Saudi Arabia to Egypt, under the Mediterranean and into Europe. Actually, it later passes just 2km from my home in Cornwall before heading out over the Atlantic to America. When President Mubarak, in his last days, shut down the Egyptian internet, you can bet there were high-level phone calls from Riyadh, Brussels and Washington DC instructing him not to shut down that pipe. Had he done so, the world could have pitched into another serious financial crisis. The Palestinians would probably have survived it better than most – survival is one of their acquired skills.

You must be logged in to post a comment.