I didn’t expect to be alive today. Yet here I am and here we are, and this is it. We’re a quarter of the way through the 21st Century.

Born mid-century in 1950, it’s rather an age-marker for me. In my twenties in the 1970s, I didn’t really expect that the world would still exist in 2025 – it seemed an age away, and back then the world’s prospects seemed very much at risk. They still are.

It feels as if I’ve lived several lives since then. A new one started in 2019. As a cancer patient since then, I haven’t expected to be alive now either. Five years ago it felt like I’d reached the end, with just one year left. My body was on its last legs, wrung out with pain, I felt like a ninety-something and it seemed as if my angels were close, eyeing me and laying the tracks to receive me.

Or perhaps they were hovering there discussing what to do with me next. Two years later, reviving from a crisis, I woke up one morning with a voice in my head, saying, “Ah, there’s something more that we’d like you to do…”.

Here I am, wondering what’s next. Life is still very provisional. I have a form of blood cancer that can’t be holistically melted away, medically cut out or irradiated. It has permanently changed my body, giving me partial disablement and about 7-8 different side-issues. It’s called Multiple Myeloma because it shows itself in many diverse forms in different people, though it particularly affects the bones – it’s also called Bone Marrow Cancer.

Things indeed are provisional: recently I took on a booking to speak at a conference in May and I wondered what state I’d be in then. However, I’m accustomed to performing in whatever state I find myself in, and if I’m wobbly and unwell I’ve found that, onstage, I can nevertheless be right on form, with my thinking, planning mind already nudged to the side. So unless I’m actually dead, the conference talk should be alright.

But I still get anticipations and, over Christmas, I worked through a good few of them – one being a fear that my cancer might be spreading and becoming something else, something more. I’m having tests later in January.

To be honest, the fear comes from a creeping feeling that whatever happens next might be too big for me, that I can’t handle it. It’s precipice-fear, ‘little me’ stuff, and the kind of fear a little boy gets when looking up at the big, wide world, feeling overwhelmed by the prospect of getting to grips with it all. I spent a few days grinding through this stuff. Then I started emerging from the other side as the newmoon came.

In life, having been through quite a lot of grinding and scraping, I seem to have made it through. So there’s a good chance I’ll make it through the next lot, somehow. They call that resilience. Though, for me, it’s as if that resilience is rooted in a strange mixture of wobbly vulnerability and an accumulated knowing that I’ve done it before and I can do it again.

If I work through my fear in advance, I tend to unmanifest whatever I fear because I’ve already faced it – or at least I start facing it and showing willing. Or it becomes changed, turning out differently and easier than it looked. Or it becomes advantageous to feel the fear and do it anyway, since it then becomes a nexus of breakthrough. I learned this in conflict zones: I’d shit bricks before I went and often I’d be dead calm and on form when I was in the middle of crunchy situations. There were only some cases of bullets flying (I was quite good at not being in places where trouble happened), but there’s a lot of chaos, tension, mess, pathos, pain and complication in conflict situations, and the psycho-emotional aspect of war was very much there.

Right now, I’m not as close to dying as I have been at various times in the last five years. Cancer came during 2019 with no detectable warning, so I didn’t have to go through anticipatory tremors about cancer beforehand, like some people have to when they’re given a diagnosis. I hadn’t felt good in the preceding six months, though it had seemed like a classic down-time that I would hopefully pull out of. But then one day my back cracked while I was gardening. The four lowest back-vertebrae had softened, and in that moment they collapsed. From that moment my life was irreversibly changed. Even after that, for two months it seemed like I had a very bad back problem, though eventually a brilliant specialist in hospital identified Myeloma. Already half-dead, the news hit me really hard – also hitting my then-partner and son, who were involved too.

But when disasters strike, I tend to be quickish to adjust, crashing through the gears of my psyche and getting really real – I don’t waste time fighting it once I realise it’s a full-on crisis. There I was, in total pain, hardly able to move, feeling wretched, and the doctors were saying I had perhaps a year or, if I was lucky, I might survive – they couldn’t tell. I wasn’t expecting this.

There’s something rather special about coming close to death. Everything simplifies dramatically, and many of life’s normal details and concerns evaporate. You’re faced with the simple, straight question of surviving or dying – and the meaning of life. Is this it? Is this the end?

This simplification is a necessary part of the dying process. Many of life’s details that we believe to be important are not actually so. On the other hand, certain experiences and life-issues come to the fore – things we’re glad about, things we regret, things we missed, things we sidelined, things we got right and things we screwed up.

Many of the things that people and society judged to be wrong, bad or inadequate… well, these are the judgements, narrownesses and prejudices of the time and the social environment we’ve lived in. Things that conventional society considers good – money, success, status, property, fame – become diminished, or they flip, turning inside out so that the price we paid for them reveals itself. We might have had a million, but were we wealthy in spirit? We might have a doctorate, but did we really understand? We might have taught a thousand people, but where have they gone?

It depends on how we respond to the arrival of death, and a key part of this is forgiveness of others and of the world, for what they did and didn’t do. There’s also self-forgiveness for all, or at least most, of the ways we have let ourselves down, got our hands dirty or avoided the main issues and the bottom-line truths. Forgiveness lets new, non-judgemental perspectives come through – seeing how things actually were, from all sides, as seen in front of the backdrop of posterity. This deep simplification and clarification is a necessary part of the dying process, and the more we can accept it and make it our own, the better things tend to go.

The more we have faced the music during our lives and amidst our life-crises, the easier this gets at death. Dying is a gradual, cumulative process for many of us, unless we pass away suddenly – it’s not just about our last breath. There’s the matter of dying before we die – going through at least some of those squeezy, grindy processes that we’ll meet at death while we’re still alive. It shortens the queue of issues that can come up around the moment of death.

When I was younger I thought that my growth would slow down in old age – this is not so. It’s going like the clappers. My capacity to process emotions and profound issues has slowed, though it has also deepened to compensate. Nowadays, when faced with a crunchy issue, I need more time to process it through. But there’s a cathartic element to it that makes it easier – a bit like writing a resignation letter and having done with the whole thing. So the big let-go and the forgiveness process seem to accelerate inner growth in the final chapter of life.

Strangely, in late life, recent memory fades relatively and longterm memory comes forward. The recent and the more distant past rearrange themselves, taking on a different perspective. I’ve found myself working through issues deriving from decades ago, together with lifelong patterns that are exposed by things happening now, and sometimes by feelings or memories that blurt up from the hidden recesses of my psyche. In late life we’re strongly encased in our patterns, laid down, routinised and reinforced over the decades, like clothing we can’t quite peel off.

After all, if you are, say, 72 years old, you’ve eaten over 26,000 breakfasts. There’s not a lot we can change because it’s already done. The consequences are with us and there’s no Undo button. But that stuckness in our karmic patterns can be repaired too, if we let it.

We can change our feelings, our standpoint, by learning from the lessons that life has thrust at us – the deeper, more abiding, more all-round lessons. In the end, there is no right or wrong to what has happened in life, though there certainly are consequences – and that’s where our choice and options lay. But it was done, time has moved on and the page has turned.

It was as it was, and now there’s the future, and whether we actually change our behaviours, beliefs and befallings. We need to sort it out with ourselves and with others, if that’s necessary and possible, or accept it, or change the way we feel about it, or own it, or drop it – or do whatever brings some sort of forwardness. That’s a key aspect of life on Earth: living in a perpetually-changing dimension of time and creating forwardness out of the situations we encounter along the way.

If only it were that simple. It’s so easy to forget and lose our way. We get brought back to it when we get to the end of our lives. What was all that for – that life? Am I happy with what happened? Have I become something more than what I was when I started? Did I do what I came here to do?

I’ve been a good boy and a bad boy. I’ve done things I feel happy about and things I regret. I’ve helped a lot of people and hurt a good few. Some things I got right and some things I misjudged. My feelings around all sorts of things have changed as life has progressed. Mercifully, it seems to get lighter as I sift through the piles of detritus left over from a life that has been lived, committing it to posterity one spoon-load at a time.

Though I’ve had a few close runs with dying since getting cancer, a funny thing has happened. I’ve gone through an unexpected inner rebirth – not ‘getting better’ but, as Evangelicals would put it, being born again. The consequence is that, as my spirit-propped condition has improved, life has become more complicated. Part of me seeks that, because I’m not one who can easily sit around weighing down seats, acting like a passive old crock with his head plugged into a TV. Being a passive care-recipient doesn’t turn me on at all.

Partially the complexity comes at me from the world around, even though it’s me unconsciously manifesting it – recently I’ve been getting five friend requests a day on Facebook, presumably because an algorithm decided I’m a somebody. Oh, thanks. I do like friends, but keeping track of it all is beyond me now. To me, a friend is someone who mutually brightens up my life like I might theirs. (Please ‘follow’ me instead!).

I’ve even been setting a few things in motion. Whether they will work is another matter, since I cannot organise them myself as I used to. The three main ones concern the Tuareg, the Sunday Meditation and the ancient sites of West Penwith.[1] My likely short shelf-life, being unpredictable, and the dysfunctions of my brains, make me thoroughly unreliable in organising things.

Also, there’s not a lot of point starting something if it subsides when I pop my clogs. So I’m scattering some seeds of possibility for other people to take care of, if they will, to see whether or not they take root. Which they might, or they might not, and that’s okay. As a reserve option I’m leaving a biggish archive of work online in case someone picks it up, sometime in the vastness of the future. There’s a remarkable loss of control that accompanies dying, and this is one aspect of it.

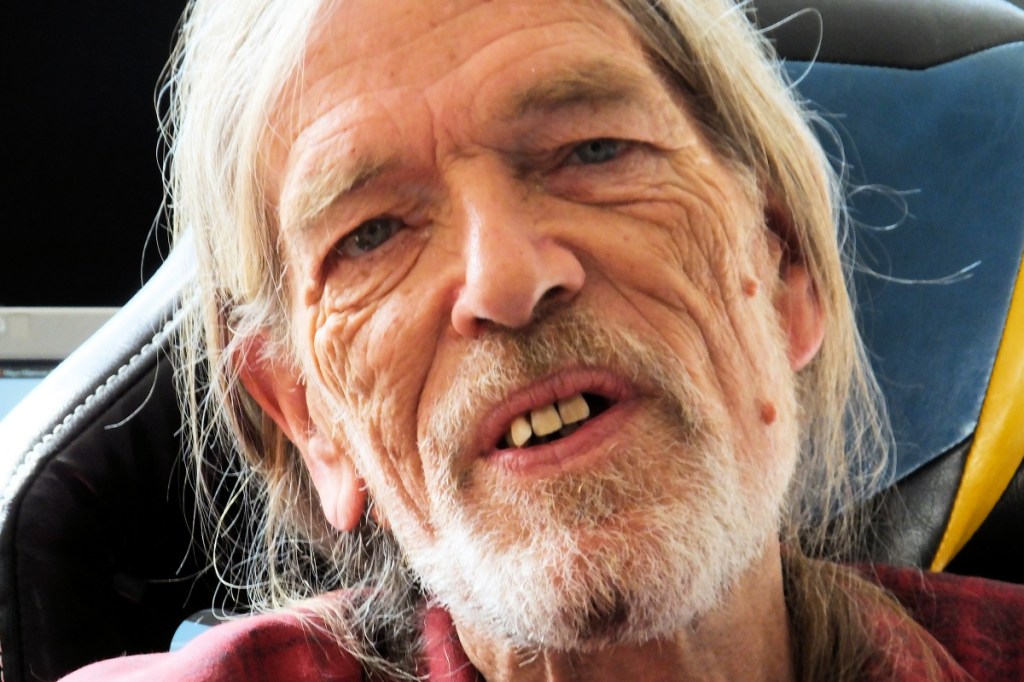

So dealing with complexities has been quite a big one. I’m asked “How are you?” seven times a day. The answer is, “Well, I’m like THIS, really!” Do you yourself do a systems-check seven times a day to monitor your condition, and can you articulate it in words each time? Even so, I appreciate your concern and good wishes, and I write these periodic blogs to let you know how I am. When they stop, you’ll know I’ve gone, or I’m on my way.

I’ve written before about dying being a gradual process, and I’d call myself seventy-ish percent dead at present, and stable (as it goes) – I go up and down each day. Today (Wednesday 1st January) I’m working myself up for a hospital visit tomorrow for a three-monthly check-up, and a generally friendly but virologically-dangerous period of waiting for it in waiting rooms. Meanwhile, my stalwart friend Claire will sit outside in her car, reading books and twiddling thumbs in a shopping-mall car park – very exciting. I have to work myself up for events like this, and the day after I’m often rather wiped out.

It’s worth thinking about this continuum. Yes, part of you is already dead. That is, part of you is in the otherworld, where your soul, in the timeless zone, is closer to eternity than you currently feel yourself to be. This is of course an illusion – it’s more a matter of where we place our awareness and what we give attention to while we’re alive. That’s one reason I do the Sunday Meditations: to give busy people a manageable, uncomplicated, regular time-slot in which to give the soul a little attention. Do it for a year and you’ll have done it fifty times. It’s like a weekly shot of cozmickle multivitamins. Good for helping face life and its rigours.

Oh, and by the way… lots of people use funny ways of talking about dying, as if not wanting to mention or face it. Like, ‘passing’. Be honest: it’s called ‘dying’. It happens to all of us, inescapably, and you’ve done it before. Even Elon Musk won’t be able to buy himself out of it, on Earth or on Mars. It’s an integral part of our life-cycle, just like getting born. In the Tibetan way of seeing things, the whole of our waking lives are equal in experiential magnitude to the apparently much shorter processes of getting born or getting dead. It’s all about experiential intensity.

During life, moments of crisis that come up can be rather like dying. They’re moments when time stretches in duration while compressing in intensity, when everything comes to a head, crunching together – and these climactic experiences are our training for the expanded moment of death, when we transit, float or squeeze ourselves into another world, whether in peace or struggling with it. How we deal with our crises in life has a big effect on how we deal with our dying. We can make it easier or we can make it harder. The funny thing is that, though dying involves a complete loss of control, it involves possibly the biggest choice and free-will opportunity of our lives since we got born.

My Mum did that. At the end of her life, at age 92, she just could not handle more hospital stays, medications, discomforts and indignities. She made a big decision to stop taking her medication, and she was gone in a few days. Good on you, Mum: you made that choice. It was a big choice, and you did it. Believe me, my Mum wasn’t into meditation and cosmic stuff at all but, in the end, she exercised her choice, a soul-choice. I have a feeling she has flowered in the otherworld.

With love from me, Palden.

PS: a blog about the Tuareg will come soon.

JUST ONE FOOTNOTE, this time:

- The Tuareg: http://www.palden.co.uk/the-tuareg-of-mali.html

The Sunday Meditation: http://www.palden.co.uk/meditations.html

Ancient Sites in Penwith, Cornwall: http://www.palden.co.uk/ahanotes-penwith.html

You must be logged in to post a comment.