I grew up in what in the 1960s was a violent and polarised city, Liverpool, learning in my teens that, in any conflict, it always, always takes two to tango – even when one side is the victim and another the oppressor. This can be a difficult issue to see and to own, whether or not one is involved in a conflict, and especially when people suffer horribly. There’s a natural tendency to take sides – and taking sides is important because issues and principles are involved in situations like Ukraine today, or in any conflict, big or small.

It is possible to take sides, or to stand up for one’s own interests, while also acknowledging that it takes two to tango. This is a key element in war strategy too: right now it is not good strategy for Russia and NATO to provoke each other too far, since they risk starting an action-reaction escalation reaching levels that fundamentally self-harm each side and everyone.

This has a restraining influence – deterrence. It can happen in the personal sphere too, in our own arguments, even with ourselves. It is a key element in peacemaking: both sides are in some way responsible – even if the balance is 80-20 or 70-30. We can support one side for entirely valid reasons, while ‘tango’ holds true nonetheless. War is filled with paradoxes.

There’s an ugly reality getting acted out in Ukraine, the ‘theatre of war’ for today: to quote Bertrand Russell, ‘War is not about who is right, it’s about who is left‘. This looks likely to prove true in coming months or years. So a miracle solution is needed here.

Talking of viruses, have you noticed how, when one war (such as Afghanistan) comes to an end, another seemingly unconnected war (such as Ukraine) can quickly start up? The issue here is that we have allowed the war virus to be firmly rooted in the human psyche, such that it becomes default behaviour. When the host population is worn out, the virus hops to another vulnerable population, until we change the default pattern.

So, immunologically, by addressing the factors that feed the war virus and the vectors of its transmission, and giving extra support to ‘medical interventions’ such as peacebuilding, diplomacy, de-traumatisation and citizen contact across the lines over a period of time, so that a new immunity can be built up. But to do this the media need to focus on peacemaking, not the excitement of conflict, and at least half of negotiators and peacemakers should be women, and the voices of the young should be heard.

One of the most dangerous things in our time is polarisation, during a time when, to address the main issues in the world, cooperation is more necessary now than ever – globally and, despite Brexit, Europe-wide. Social consensus, cooperation and human care are so much needed – this was demonstrated during the Covid lockdowns. Environmental, climatic, population, social and justice issues will make little progress without care, pluralism and inclusivity. This means consensus not only amongst our lot, but also with that lot over there – even with banksters, extremists and other demons.

There’s a further thing: when people and nations are getting on with explosions and atrocities, they are not getting on with the essential questions that, in the end, harm us all. They are blasting out the subtle, tender, human aspects of life with noise and violence. War is a tragic diversion, a terrible habit of humanity that is used unconsciously, and by elites, as a way of evading the big questions. It’s ingrained in all of us.

This applies in our personal relationships: each party in an argument might consider the other wrong or flawed, feeling justified in standing up for itself, yet both parties together fail to fulfil the core purpose of their relationship unless their argument progresses toward resolution. This doesn’t mean everything has to be peaceful and smoothed over: differences of position need sorting out at an earlier stage, before they get complex and damaging, in the knowledge that fighting charges a higher price to both parties than reconciliation. Fighting rarely sorts out the fundamental causes of conflict, instead laying down further historic pain and trauma for future eruption and processing. It goes on and on.

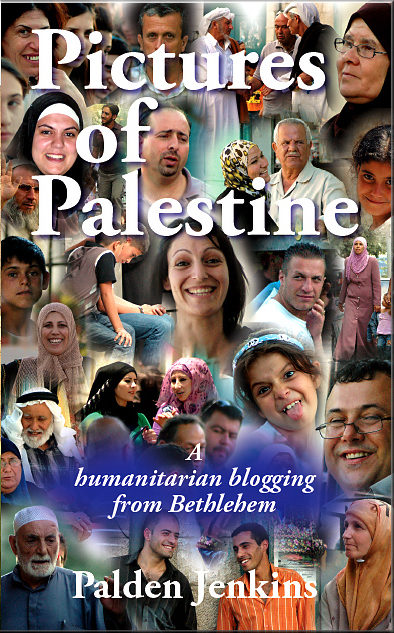

This said, I honour, respect and support the choice of Ukrainians to resist, now that we are where we are. I would too, in their situation. I’ve spent years working with Palestinians, and I feel their resistance is justified, not because I believe Israelis are wrong but because, ultimately, what the Israeli state has been doing is not right for Palestinians, Israelis or anyone. If I were in Ukraine, I’d be in the resistance – in my case, doing furtive and dangerous things in the background (I have Mars in Scorpio).

Would you keep your head down, be a refugee or join the resistance? It’s quite important to be honest with ourselves about questions like this, at this time.

One strange thing about war situations is this: it gives people a tremendous, if tragic, opportunity to discover their true gifts. It’s a free-for-all in many different senses, and some of the acts of humanity I’ve seen in conflict situations are unforgettable. And people quickly find out what they’re really good at.

Polarisation, a virus of the psyche, has no simple vaccination. It oversimplifies things when a conflict escalates and breaks out, even if it is but a conflict of ideas or values. Conflicts are a complex calculus, often going way back into histories and threads that otherwise have been forgotten. When they break out, the rules change drastically and damage and pain escalate horrendously as a result. Referring to the past to justify one’s position becomes less and less relevant because, in war, the past few days’ damaging events can override them.

In the end, apart from fighting to exhaustion, the only way to resolve a conflict is to focus on the present and future needs of all concerned parties, because that’s what’s being forged and the outcome is longterm or permanent. To some extent, everyone is right and everyone is wrong, and this needs recognising. If we cannot establish these as global norms, we will not really resolve the bigger issues we face in the 21st Century. It’s that simple.

Ideas and sentiments replicate virally and, although some folk, and some countries like Britain, see themselves as scions of freedom, they can also be obedient carriers and sufferers of the polarisation virus without really knowing or owning up to it. The same applies to people who buy into conventional public groupthink, which settles so easily around simple catchphrases, formulae, heroes or villains, denying wider perspectives, tending to see things one-sidedly and seeking to pre-decide issues. Driven by an urge for comfort in numbers, individuals can suspend consideration, subscribing instead to verified and authorised rationales made official by the loudest pundits, or by convention, or by authorities or corporates with the power to persuade or control, both in the foreground or the background.

When social control mechanisms rear their heads, as we’ve seen in recent years, we tend to blame governments, corporations, Big Brother, Reptilians, foreigners or whatever, yet thereby we confirm our own infection by the virus, helping to replicate it. People accused of wrongs are too easily demonised, stripping them of humanity, so that others can feel they’re right. Poor thinking, often befogged by reverberating public sentiment, is so easily captured and trained, and our media and social media excel in it.

The virus arises from a kind of separation trauma deep in the heart of humanity. It emerged as competitiveness, warlordism, stratified social power, a sense that others are a threat and that nature is there for conquest, accompanied by an increasingly cultish elevation of self-interest. In Britain I think it took hold around 1200 BCE, at the end of the megalithic era. Different people are differently affected by the polarisation and groupthink, and to step outside their thralldom can be quite traumatic because all our beliefs, our world, can disintegrate – which is why many people don’t do it. Best done in youth, though it’s a struggle then, too.

In this respect, I recommend spending time outside the developed world, not as a tourist but in the villages and streets, and not just for a week, and running on economy – things look and feel very different. Learn how to sleep on the ground, cook with one pan on a fire or how to accept the generosity of quite poor people.

I’m writing all this not only as a geopolitics and history buff, but because I’m personally in a deep and moving conflict of my own in my life right now, and the challenge is to remember all the above in my dealings. This is difficult – stepping outside myself sufficiently to be as objective and fair as possible, yet standing up for and successfully communicating my own position and terms at the same time. It’s a matter of feeling my pain, guilt and fear while, as much as possible, not being dominated by them. Sometimes I succeed, sometimes I don’t, and when I fail it adds to the hurt I cause.

It’s strange too since, as a cancer patient, I have to be more attentive to my needs and interests than ever before, and I’m in new territory. It presents a dilemma. I need others’ support like never before, though I’m not up for playing the victim cancer sufferer either – an attitude that has a downward bearing on my health and spirits. I have no right to expect others to make sacrifices for me, only a hope. I’m at risk of getting mashed even by others’ often quite normal, acceptable actions and ways, bless them, and particularly by their non-actions or omissions. Yet, up to the right level at least, I do need my minimum needs met, without lapsing into a stuck constellation of relationships where I’m asking favours and demanding support of a time-pressed circle of rushed helpers, neighbours, friends and family, most of whom are doing their very best, and for whose inputs I’m genuinely grateful.

Yet in our society helping others is seen as a choice, carried out when we have time or inclination, when in many societies it is a natural obligation and priority. In war, it’s all hands on deck or get out of the way. Indeed, it’s likely to be all hands on deck in coming decades, though not necessarily because of war. Evolving a balance between freedom and obligation is one of the great tasks of coming decades: the balance of private preference and wider benefit, local and global, and human needs and ecosystem priorities. And it has to work, otherwise it’s hard times.

So in my heart, the war in Ukraine (also in Sahel and Palestine) and the difficult personal conflict I am in, are digging over similar ground. It’s literally heart-rending. In moments of despair, part of me even wants to go to Ukraine, not to fight, but to weigh in on making people happier and doing some backchannel work – I have the experience, and an old cripple on sticks like me is quite good cover when hobbling through checkpoints and handling scrapes. I’m likely to die before too long anyway, which means that, though I do have fear, it doesn’t impact quite the same as it usually would – and you gotta go somehow.

But I don’t have it in me to go, really, physically and financially. My time for that is past, and sometimes I go through pangs about that. So, I’m doing what I can from here, re-engaging in a new level of psychic work, from my eyrie here on the farm, and from occasional hilltops and headlands in West Penwith. I find the Kremlin is psychically not as well guarded as the White House or even Number Ten.

This confluence of personal feeling and war in Ukraine is interesting because, while currently experiencing my own pain and loss patterns, my geopolitical inner efforts are able to come from a more deep and feelingful place, and both are somehow inwardly connected. Many Ukrainians, like cancer patients, have death hovering close to them, and there’s a deep vulnerability and a bizarre openness to that. This is what part of me has deeply sought, in my involvement in conflicts in the past – a sensitivity and emotional permeability that makes me more human, and it comes up in risky, edgy situations.

I’ve sought this in loving and caring relationships too, only to come up against my own limitations, pain and switched-downness. I’ve made some progress, but in truth I can’t say I’ve resolved the matter at all. I look and sound pretty sussed out, but really, I’m both happy and unhappy with the way I’ve handled life and its ins and outs. I haven’t fitted easily into the world. It’s good to be honest about that because, when we come to dying, the whole story of our lives show themselves in a new and different way, and it’s better facing awkward truths beforehand. It’s not self-pity, it’s straight old reality-as-it-is being revealed, and ultimately that’s relieving, helping with karmic untangling.

And life goes on. In health I am kinda okay, with room for improvement and a few problem issues that trouble me, but I’ll get there. In spirits I am soldiering on and holding up, and I’ve been having some lovely adventures out in nature – and I keep looking for the gift in situations. Astrologically I’m on a few big Saturn transits, so whaddya expect?

Springtime is coming here in Cornwall, and some bonny days have appeared since newmoon, and the plants are yawning open, and the geese will probably head north soon, and the tweety birds are chomping birdseed and fatballs at a rate of knots, and it’s no longer dark when I wake up, and Saturday was the first day I didn’t light my woodstove in the morning. And I enjoy blueberry porage for breakfast.

Amidst the hurricane of flying crap happening now, above all hold steady – and I shall too. This is the second of quite a few big crises in the 2020s, and it’s best to forget ‘normal’ and to develop new ways to find our ground. Here’s a re-tweet: I sense that the future is having an increasingly causative effect on the present – the past is getting wiped away faster than we would like. We’re getting sucked forward into successive cliffhanger situations where we, as humans, are obliged to make bottom-line decisions – kinda last-chance saloon stuff. Perhaps this applies to my personal affairs too, or perhaps to yours. Such brinkmanship is a way to prepare us for change, because guaranteeing the future involves making a quantum leap where absolutely everything is up for review and change, and we’re all involved. It’s hair-raising and gives no security, and it’s what we’re being confronted with now, in the 2020s.

Love from me, down’ere in Cornwall. Palden.

My podcasts are at www.palden.co.uk/podcasts.html

And all my stuff can be found here: www.palden.co.uk

You must be logged in to post a comment.