A Bronze Age gathering place in West Penwith, Cornwall

Palden Jenkins, June 2025

Recently I was at Caer Brân (pronounced Ker Brayne) on a Belerion Project field trip. Nowadays partially disabled, I hadn’t been there for years, even though, when I look out of my window from my desk, it’s on the ridge over the valley, less than a mile away. So I gaze at it a lot.

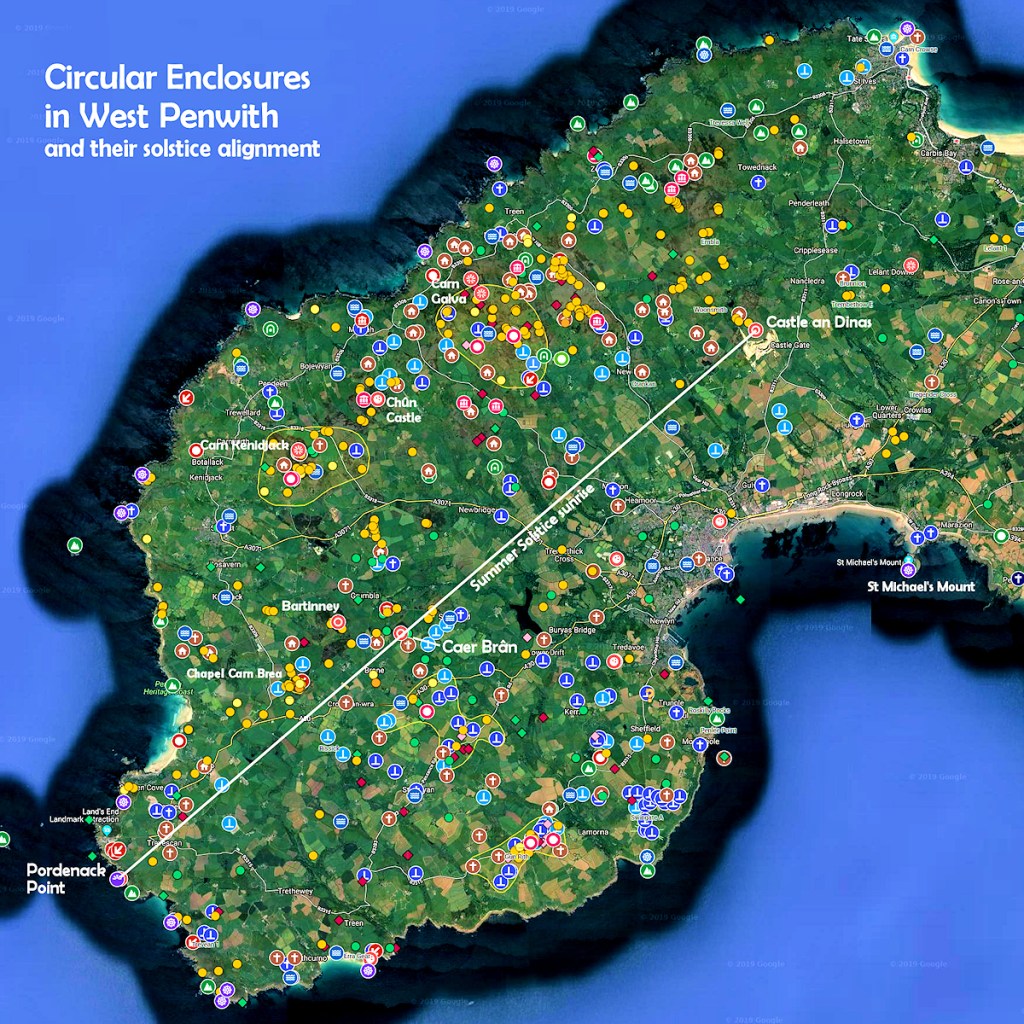

In former years I had come to the idea that, in the Mid-Bronze Age, Caer Brân served as a kind of parliament site for the whole of Penwith. This came to me after news came out some years ago about a circular enclosure, found using LIDAR scanning, on the cliffs at Pordenack Point, just south of Land’s End. This revealed something: Pordenack, Caer Brân and Castle an Dinas, three circular enclosures, were built in a straight line, oriented to the summer solstice sunrise.

This suddenly gave these three sites a lot more significance than had been seen previously.

However, if we take a line from the centre of the Pordenack clifftop enclosure to the centre of Castle an Dinas, it passes through Caer Brân though not accurately through its centre. It passes across the southeast side of Caer Brân, though within the enclosure. I’m not sure whether there is any meaning to that, but these details are worth observing.

At ancient sites, the main thing I do is a kind of psychic archaeology. That’s not as esoteric or complex as it sounds. All I do is sit there, relax, give it time, and I let feelings and ideas come up. It’s not a matter of trying, but of allowing. Often I use a pendulum, which helps engage both thinking and intuition. I do this in two ways, flipping between them: I use a pendulum while doing ‘intuitive free-thinking’ – it indicates when I’m ‘on track’ or ‘off track’ – and also I ask specific questions about details and dates, seeking a Yes/No answer. I note it all down or speak what’s coming up into a sound-recorder.

As an historian, I’m attentive to historic plausibility before jumping to conclusions arising from these ‘subjective’ researches. Mistakes can often be made in the interpretation of impressions and ideas, more than in their initial psycho-intuitive reception. It’s important to avoid allowing existing ideas, knowledge and preferences to shade and bias such findings, though it’s important afterwards to see how new insights fit with foregoing ones – if indeed they do.

If they don’t somehow fit, then the observation might either be incorrect or something is yet to be discovered that will make sense of it. In one case I had to wait twenty years. You get surprises. Findings might at first make no sense, or no concrete or logical evidence backs them up, but later on things can fall into place. So for much of the time they remain working hypotheses, not facts. One trick is to consider their plausibility and whether they shed light on anything else. Some archaeological findings suffer this problem, or their interpretation is conjectural – as is the case with a few seemingly authoritative statements on the signboard below Caer Brân (more below).

Here are some findings from my recent visit to Caer Brân.

It seems to me that it is not the inherent earth energy of this place that matters, as is the case at a stone circle. There isn’t the same sense of energy here. It seems that the landscape positioning of Caer Brân matters more: there’s a strong visual connection with other key sites in Penwith and beyond, including Scilly, the Lizard and Carn Brea near Redruth. It has a wide, thirty-mile panorama.

Very noticeable are the sightlines from Caer Brân to Neolithic sites which, at the time of Caer Brân’s building, would themselves have been regarded as ancient – about 1,800 years older than Caer Brân.

All of Penwith’s Neolithic sites are visible except Trencrom Hill. Carn Kenidjack and Carn Galva poke above the horizon as if placed there by an enormous geological chess-player’s hand; Carn Brea is distant yet prominent; St Michael’s Mount sits resplendently down in Mount’s Bay. The Isles of Scilly hover in the gap between Chapel Carn Brea and Bartinney Castle. So visual connectedness with other sites was clearly important. Caer Brân is not prominently visible from these sites – it’s a one-way visibility.

Apart from sightlines, it has several alignments (leylines) associating it with other ancient sites, yet these are largely rather unspectacular except for two. Alignments don’t seem to be a dominant factor here – sightlines are more important. (Click for an alignments map of Penwith.)

One alignment (83) goes from the summit cairn on nearby Chapel Carn Brea through Caer Brân’s SW edge to St Erth church (on an Iron Age round that might be older) and finally it heads for the Neolithic tor of Carn Brea.

The other (199) goes from Cape Cornwall to Caer Brân, then to the Blind Fiddler menhir and Kerris Round, then over Mount’s Bay to Predannack Head, a clifftop site on the Lizard that feels a bit like a geomantic control tower – it’s worth a visit. The first alignment links two Neolithic hills and the second links two major cliff sanctuaries.

Caer Brân doesn’t feel like a high-energy place, though it does have atmosphere. However, as a former gathering place, it feels to me as if it misses the human attention and ‘hwyl’ that it once witnessed and hosted. (Hwyl is Welsh for fun and stirring, special experiences).

Archaeologists commonly use the term ‘ceremonial’ for sites like this, but this is inaccurate. This was a gathering place, a people place. The enclosure uphill on Bartinney Castle was clearly ceremonial and magical, but I believe Caer Brân was mainly social in character and purpose.

These two adjacent sites, hardly a mile apart, formed a pair – Bartinney more spiritual and Caer Brân more worldly. During their moots, people assembled at Caer Brân probably trooped up to Bartinney for the spiritual high point of their gatherings, or to seal the deal. Tradition has it that inside the enclosure on Bartinney evil cannot touch you.

Sancreed Beacon, Caer Brân and Bartinney, arrayed along a ridge, were part of a local landscape temple also comprising Botrea Hill, Chapel Carn Brea and Boscawen-ûn stone circle. This ridge seems to act as a kind of fulcrum for the whole of Penwith, and Chapel Carn Brea, Botrea Hill and Boscawen-ûn anchor and stabilise it on either side.

This is all about a geomantic quality we could call ‘perceptual centrality’ – the feeling that you’re standing at the centre of everything. This is common at many ancient sites: a subtle sense of emphasised hereness and nowness that is one of their key psycho-spiritual effects. It seems odd that Boscawen-ûn acts as a peripheral anchor to this string of three hills. Yet this is how it seems at Caer Brân, standing at the centre of its own psycho-geographic gravity-field. Yet at Boscawen-ûn, sitting at the centre of its own perceptual gravity field, it seems as if Caer Brân and Chapel Carn Brea are peripheral appendages to it.

Each major site in Penwith is a gravity-centre of psycho-geographic experience. In one sense this is a perceptual matter, while in another it’s a very real, a repeatable experience shared by many people. In a pre-literate society with no maps or aerial photos, people were psychologically part of their world and it was part of them. They perceived their world differently to us.

This was particularly so in the Neolithic. As the Bronze Age progressed, man-made landscape expanded in extent and people started developing more of a sense of mastery of nature rather than of being guests in it. Even so, their ancient sites were stretched over and fitted to nature and the landscape without imposing on them. Bronzies’ nature-interventions were largely sympathetic. Rampant resource exploitation came later in history.

On the signboard downhill from Caer Brân I think they got a few details wrong. They associate Caer Brân with Carn Euny, a nearby ancient settlement, suggesting that the villagers had built and used it. That’s logical, though I think it is incorrect.

The impression I get is that Caer Brân was a Penwith-wide social-infrastructure project. People were called up from all over Penwith to build it. It was to be a neutral space, owned or hosted by no individual clan. It was to act as a meeting place for all of the Penwithian clans, or their representatives. It’s possible there were around ten clans.

Its geographic centrality in Penwith and its location at the crossroads of two major ancient trackways are clues suggesting this (see trackway map below), together with the solstice alignment of the three circular sites. So while Carn Euny looks like a logical ‘owner’ of Caer Brân, I don’t think this was so. Neither was Castle an Dinas, Penwith’s other big gathering site, controlled by one clan. It is likely it was built around the same time as Caer Brân, and that they were built with different purposes in mind.

Using a pendulum, I asked how long it took to build Caer Brân: I got ‘two summers’. That was surprising: I expected longer (such as five years). This would have involved quite a mobilisation of available hands and backup support, including supplying tools and food and maintaining life’s normal demands back home. They wanted to get the job done quickly.

Perhaps there was an urgent need. Perhaps they had reached a kind of political juncture in Penwith, where a pressing need came up to reorganise things, reflecting emergent needs and realities. Or perhaps there was a generational shift in a time of social change and population growth, necessitating the building of new gathering places.

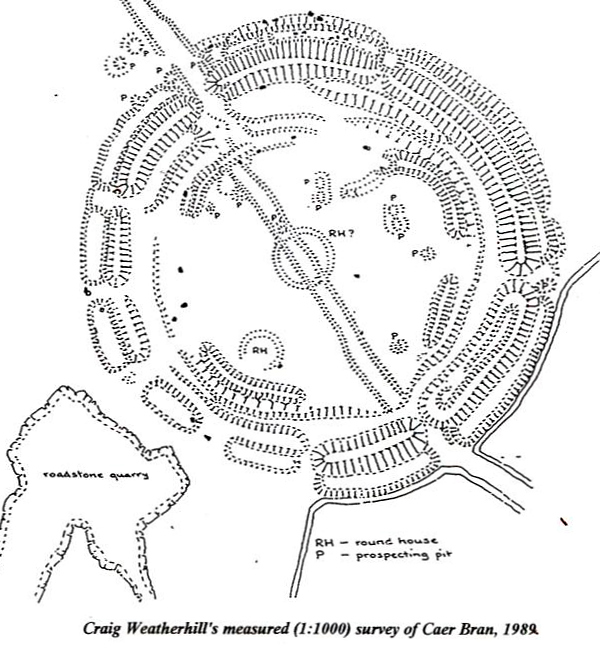

The signboard got one thing right: the ‘ring cairns’ inside Caer Brân are older than the enclosure. I date-dowsed them to the 2200s BCE, while the enclosure came 400ish years later in the 1830s. Except that the ‘ring cairns’ were roundhuts. The one in the centre of Caer Brân gave me the sense of a Hopi Kiva, a place for focused magical-spiritual work – I got the image of a crucible. It was placed there not because of a major energy-vortex at that place, but because of its visual, almost geometric connections with other places in the wider landscape.

I found that three main gatherings were held each year: on the fullmoons around Imbolc and Lughnasa, and another in early December. I asked why this third one was not at winter solstice and got a straight reply, ‘Everyone wanted to be at home then’. Well, indeed. And since fullmoons light up the night, often marking shifts in the season or in weather patterns, the Bronzies were probably not as concerned with exact cross-quarter days as with the fullmoons near to them. The moon provided no-cost solar-powered lighting. And a taste of magic.

The climate was a bit warmer then, less windy, stormy and Atlantic-dominated than it is now. This changed around the 1200s at the end of the Megalithic period – the jetstream moved south, bringing more wind, rain and changeable weather. It made sense in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages to be on panoramic hilltops like Caer Brân. In the Late Bronze Age after 1200ish, people moved downhill, abandoning or sidelining many of the megalithic sites.

Date dowsing suggests that Caer Brân was built in the 1830s BCE and was in use until the 1330s. This is longer than archaeologists reckon – it’s that signboard again. They give Caer Brân a short active life, on the basis that a gap in the ‘ramparts’ in the southwest of the enclosure represents an unfinished segment, and that, ergo, the enclosure was abandoned at the end of its construction.

This seemingly logical conclusion seems to me to be flimsy. Abandoning a project that is 95% complete is a bit strange. The abandonment idea was probably adopted in the days when archaeologists saw Caer Brân as a ‘hillfort’ built for defensive purposes. But, nationwide, the majority of hillforts were not built for this – especially in Penwith, where there are no signs of prehistoric conflict. There is no evidence of outright abandonment of Caer Brân either – it’s a best guess. No, I think that gap was deliberate. However, I cannot figure out why it was built so, and this question needs more work.

While we’re here, it’s worth observing that the second roundhut toward the southwest edge of the enclosure, marked on Craig Weatherhill’s survey, is also at the crossing point of four local alignments and close to the Pordenack to Castle an Dinas solar alignment, which crosses Caer Brân off-centre. From this we can surmise that this was probably no ordinary residential roundhut, instead having some sort of magical meaning. If alignments pass through a roundhut, in my experience it is likely that it was not residential in purpose.

In a moment of vision, I saw twentyish elders sitting in an arc, presiding over long discussions. I feel this was the political meeting place in Penwith. What came to me was this: it took until 1800 BCE to build Caer Brân because only by that date had the newly-colonised south of Penwith really been fully established. The south was colonised in the Bronze Age as population grew and bronze tools for clearing trees and land came into common use, probably around 2200-2000 BCE. A gradual southward population move would follow, shifting the balance of population. Until then the traditional power centre was around Chûn, Carn Galva and Zennor Hill in the north.

So by 1800 the centre of gravity had shifted south. The Boscawen-ûn and Merry Maidens stone circle complexes had been built, together with strings of menhirs, and the area had been opened up. By then, about half of Penwith was forested. Areas were cleared with landscape perspectives and sightlines in mind – these avenues highlighting features in the wider landscape were a key part of an ancient site and the geomantic thinking behind it. The Bronzies were not the nature-rapists that we moderns have become, and felling trees manually and harvesting their timbers was a big, slow job. They did it thoughtfully, needing to keep the gods and spirits happy too. So they felled trees selectively, creating a parkland landscape with open, grazed areas and patches of wildwood.

This is probably why it took until 1800 BCE for Caer Brân to be built. Only by then did people realise there was a need for it. Or perhaps only then did the perceived need override the inertia of carrying on as they’d always done. It’s the connectedness and centrality of this place that is a large part of its reason for being. But in the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age it was not central to people’s lives – it became so in the Mid-Bronze Age, by 1800 BCE.

Castle an Dinas, Penwith’s other big gathering site, is very visible from Caer Brân. The summer solstice sun rises above it. Clearly they were connected, though they probably served contrasting or complementary purposes. There is evidence of trading at Castle an Dinas, and it is likely that it hosted gatherings at other times of year such as Beltane and Samhain. Two astronomical alignments from its centre suggest this: one to Trencrom Hill and the other to Conquer Cairn. Gatherings were possibly held at summer solstice too – suggested by the solstice alignment from Caer Brân. I get the feeling there was more socialising and celebration at Castle an Dinas than at Caer Brân. Perhaps Castle an Dinas needs further investigation.

Caer Brân stood near the crossroads of two major trackways. So I think this is an ideal place for a kind of parliament, for decision-making moots and occasions for the settling of inter-clan issues. Decisions would not only have involved discussion but also deep-level processes, consultation with the gods and the ancestors – perhaps up on Bartinney. There would be meetings with relatives and old friends from around the peninsula, social rites, discussions and late-night ceilidhs around campfires – a festival for a few hundred people, for 3-4 days.

Downhill there’s a smaller, non-circular enclosure. I asked what this was for. A simple answer came: animals. I saw two possibilities. In between gatherings they probably kept animals in Caer Brân to graze and mow it, moving them down to the lower enclosure for the duration of a festival. Alternatively, when horses came into use around the 1500s, it was where they kept the horses. In other words, methinks the lower enclosure was built to serve practical purposes.

The Belerion Project is a citizen research project and stream of consciousness in West Penwith. We seek to encourage psycho-intuitive investigation of the ancient sites of West Penwith, and hopefully to make such work more systematic. It’s in its early stages at present. At minimum participants will acquire a habit of building up their skills in such intuitive work, and keeping and collating notes. Possibly, after a few years, a comprehensive body of work might emerge too – an energy survey and magical assessment of Penwith’s major ancient sites.

If it interests you to join the project and you live in or near Penwith, check out the Belerion link below and come on a field trip. This project can run alongside archaeological research and, I believe, contribute many clues. Of which I hope this study has a few!

So this has been a study of a site that is, I believe, underestimated in its significance and importance. It is very central in Penwith, and its main remains are simply a circular embankment in a prominent hilltop place. But I suggest that it was the place where people periodically assembled to discuss and sort out tribal matters concerning the whole of Penwith. And if not this, then what?

LINKS

ancientpenwith.org – about Penwith’s geomancy and alignments (the original Ancient Penwith website)

ancientpenwith.org/maps.html – maps of Penwith’s and Cornwall’s ancient sites and alignments

ancientpenwith.org/even-more-maps.html – loads more maps

palden.co.uk/shiningland/ – Shining Land, a book by Palden about Penwith’s ancient sites

ancientpenwith.org/belerion.html – about the Belerion Project

palden.co.uk/caspn.html – The Geomancy of West Penwith, a recent two hour illustrated audio talk given at the annual CASPN Pathways to the Past weekend.

You must be logged in to post a comment.